Taking better birds in flight photos

I started photographing birds in flight (BIF) in 2017 in Cape Town, having previously concentrated mainly on long exposure sea and river scapes, and street photography. I had heard that proficiency in BIF was hard and expensive, as it needed great technique plus expensive cameras and lenses for any kind of success. Seven years ago, this was very true. But much of that has now changed, and for some reason the dividing time was Covid. On my March 2024 Cape Town trip, I was struck by how my photography results had improved, and this post is intended to describe those changes in the context of the BIF photos of the Sacred Ibis. It is not very technical, but if you want to understand how this kind of photo is taken, it’s quite a useful read.

Birds in flight hit rate

A decent BIF photo has to have the bird in focus, in the centre of the frame, occupying at least half the frame, with good lighting and an interesting wing position. Pre-Covid, if I got half a dozen photos that met those criteria in a couple of hours, I would be very satisfied. Frequently I would come back with no usable shots at all. Post Covid, I typically will come back with a thousand shots that are all portfolio capable from a two-hour shoot. What has made the difference? Three main changes — longer lenses, better technique and huge improvements in camera technology.

Longer lenses for birds in flight

For any kind of bird or wildlife shot, a telephoto lens is essential. The lens “focal length” is a measure of how much the optics magnify an image. Focal lengths are measured in millimetres, and the greater the length, the more powerful the lens. Because of the geometry of camera optics, any single lens will magnify much more when on a small image sensor like a phone than on a large one like a traditional 35 mm sensor.

To enable comparisons between different types of camera, most photographers refer to “full frame equivalent” (FFE) focal lengths. To give you some comparative indication, the main camera on the iPhone has a lens with an FFE equivalent of 26mm, which is classed as wide angle. A telephoto lens is usually classed as starting above 50mm. For birds and wildlife, the minimum lens length is typically around 400mm, so massively longer than a normal camera or phone lens.

For serious birds in flight, the classic lens length is 600mm, or 23 times the magnification of an iPhone lens. The amount of glass in professional 600mm lenses is pretty huge, and the lenses are eyewateringly expensive. The Canon 600mm f4 lens weighs 3kg and costs £13,119.99. You would be surprised how many rich retired dentists (and the like) own these lenses. It doesn’t always help, however.

Even longer lenses

The Sacred Ibis is an immensely irritating bird. They remain motionless, feeding in shallow water until you get to within about 60 metres of them, and then fly away from you. This prevents you from getting a front-on shot, or one where the bird fills the frame. Over many years, I proved to myself that 600mm wasn’t long enough to photograph them. I am now using an 840mm FFE lens for these shots, or 32 times the magnification of an iPhone camera. This is a great improvement. By the way, at these lengths, to get super sharp photos, pros use fixed focal length lenses, or prime lenses, rather than zoom lenses. Zooms are very convenient, but they are never as sharp or let in as much light as prime lenses.

But professional versions of 800mm lenses make the 600mm look cheap and insubstantial. The Canon 800mm f5.6 lens costs £20,000, weighs 3 kg and is 2ft or 60cm long. Even retired dentists can’t stretch to this, and it is only usually bought by pros. How can I afford one? Well, I don’t use a Sony or Canon system, as I will show later. In the meantime, even if you have 20 grand for one of these monsters, taking BIF shots is still really hard. That’s because of the problem of the angle of view.

The angle of view problem

On an iPhone camera, you can see around 50-60 degrees from side to side, which is roughly the same as the human eye’s main focus of attention. The iPhone ultra-wide angle lens has an angle of about 125 degrees, about the same amount as the human eye’s maximum peripheral vision. By contrast, a 600mm lens has a field of view of 3.5 degrees, and at 840mm it’s about 2.4 degrees (or a quarter of the size of the lower diagram on the right). It’s the equivalent of looking down a long narrow cardboard tube.

Alternatively, imagine on your iPhone that all you have to look at is a tiny circle 1/30th of the area of the phone screen, and then imagine rapidly moving that tiny circle around to find a moving object. Pretty hard, and in fact almost impossible (on an iPhone). Now imagine trying to find a medium-sized bird 60 metres away through that tiny circle. Quite hard. Now imagine it’s already flying, and you start to see the challenge.

There are a further couple of problems with ultra-long lenses. Bird movements are very dynamic. They fly erratically, will suddenly appear and equally suddenly disappear, and they can turn up anywhere on the horizon. You can’t see all of this if you are only looking at a tiny area of the landscape.

So somehow you have to be looking at everything, judging if something interesting is happening, or going to happen, and then try to find that area through your incredibly tiny tube. That requires you to take the lens away from your eye to see the scene, then put it back and try to move it to the area of interest. As we have noted, the lens can weigh 3kg and be up to 2 feet long. We’ll come back to this factor later.

It doesn’t matter how much you spend on the lens — there is no technology at the time of writing that can help you with this problem. It needs technique and skill to be able to do this.

Long lens technique

For many people, including me for many years, the maximum focal length usable for birds in flight is 600mm and even that is quite a challenge. The skill is in being able to locate the action you want to shoot, and then put the camera and lens up to your eye and immediately find that tiny little area through the viewfinder.

There is only one way to do this, and that is to practice. Dedicated bird photographers spend hours per week practising on common birds like gulls to develop this skill, in much the same way that musicians practice the scales daily.

If it’s been weeks or months since the last BIF outing, the skill has to be practised again. Over the years, 600mm has become relatively straightforward for me, and I have now progressed to 840mm. This length is really challenging for BIF, but it seems to work for me, and all the shots in this album are at 840mm. It helps if the birds are large and relatively predictable, as with the Sacred Ibis.

Small, fast moving birds like terns and gulls are very hard to capture in flight and very few photographers can follow them with an 800mm lens. But even if you have the skill at 800+mm, there is another issue that makes BIF shots hard, and that is inertia.

The problem of Inertia

Inertia is a word rarely found in photography circles, but it ought to be used more. It means the resistance of a body to changes in motion, and it depends on the mass of the body, and its dimensions. So moving or rotating an object is harder the heavier and longer it is. This applies to BIF in a profound way.

Inertia means that the size and weight of the lens makes a big difference when the lens and camera are quickly moved up to the eye to take a shot, or rotated sideways or upwards to follow a moving bird.

This is in addition to the requirement just to hold the lens up for long periods. The force needed to hold and move a professional 600mm or 800mm lens is so great that most pro photographers have to mount the camera and lens on a tripod or monopod. That way a large part of the weight is supported, as in the photo above, where the lenses are all shorter than 800mm but are still supported on monopods.

A lens mounted on a tripod or monopod is massively less manoeuvrable than one that is handheld. For example, motion up and down is severely limited, as you have to move your head down to tilt the lens up, and you can only move a limited amount from side to side without having to step round the support. In addition, horizontal rotational inertia is increased because of the damping factor of the lens support system. Hand holding is hugely preferable, but only the very muscular can hand hold a 4kg camera and lens combination for hours. Those that do this for a career invariably end up with severe shoulder and back problems.

Whatever method used, speed of movement when using a large professional 600-800mm lens is severely limited. If only there was such a thing as a professional 800mm prime lens that was so light and small it could be handheld for hours and manoeuvred to follow even the fastest bird. If only such a thing existed!

It turns out that there is such a lens, and I’ll describe it and its associated camera system below.

The frame rate problem

Frame rate or burst rate is the speed with which you can take successive images. The essence of a good BIF shot, once the technical aspects are satisfied and the bird is sharp and large enough in the frame, is in the bird’s flight position. The challenge is to get a pleasing wing and body position, with the bird heading in the right direction. It is absolutely impossible, except by sheer luck, to get great BIF images with just one, or only a few shots. Up to a limit of say 50 frames per second, the faster a camera can take pictures, the more likely it is that a great shot may result.

Until around 2017, cameras were severely limited in their frame rates. In 2020, the absolute top of the line digital single lens reflex (DSLR) professional sports cameras from Nikon and Canon reached around 14 frames per second. These were limited not only by the mechanics of the shutter and mirror, but also by the speed with which data could be read from the digital sensor and transferred to a storage card.

In the last few years, both problems have been solved to a certain extent with the new breed of mirrorless cameras, which first did away with the moving mirrors of the DSLR. Then they moved to electronic exposure, which removed the dependency on a mechanical shutter to expose the image. However, these improvements didn’t make for good BIF cameras — in fact the reverse. The issue was that now the electronic viewfinder through which you looked at the subject could not keep up with the electronic shutter, so what you saw was always stuttering and lagging behind where the bird was. Moreover, some aspects of the electronic shutter design meant that the image was distorted (“rolling shutter”) when the lens moved quickly, so the image often looked strange.

It has taken some huge leaps forward in sensor and semiconductor technology to solve this problem. The breakthrough was something called a “stacked sensor” which was pioneered by Sony in their full-frame A9 camera in 2017. This enabled sensor readout so fast that there was no rolling shutter. It was combined with a new superfast viewfinder that could for the first time keep up with the new sensor. However, the frame rate was still only 20 frames per second — and getting to faster frame rates was a problem because of the large size of the full-frame sensor. In addition, the camera was extremely expensive and still costs £6000 today (albeit with better performance).

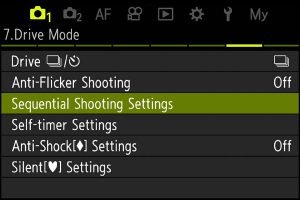

In the last two years, more stacked sensor cameras have appeared. Full frame stacked sensors with high resolution are still largely limited to 20 frames per second because of the data transfer issues, but the lower-resolution A9iii can now shoot at 120 frames per second. This number of frames is certainly overkill – 10 seconds of shooting results in over 1000 images. But the sweet spot of 50-60 frames per second with no rolling shutter or viewfinder lag is now readily achieved in several cameras at a much lower cost than the Sony A9.

So that’s everything handled, right? Long lens: check. Fast frame rate: check. Fast viewfinder: check. Unfortunately, there is one giant factor that is also needed, and that is the ability to focus on the bird. This is where perhaps the greatest breakthrough has been made in recent years.

The problem of focus

Getting and keeping a moving bird in your sights is only part of the challenge. The next job is to get the thing in focus. For years, this was the limiting factor in BIF shots. Focus systems for cameras have always worked quite well for subjects that are close up and relatively static. But making ultrafine adjustments in the elements of a long lens to get a moving subject 50-60 metres away in focus is a significant engineering challenge. Indeed, it was one that precision engineering or clever electronics could not solve. It took Artificial Intelligence (AI), or more accurately Machine Learning (ML) to produce the answer..

Birds are tricky devils. They move fast and unpredictably, they fly behind and between trees and other foliage, and indeed, foliage is their natural habitat. Until very recently, cameras only focussed on “things”, or objects — typically the nearest object it could find. The problem for bird photographers is that this object was often a twig, or rock, or tree, and not the bird. The answer was to use a small focus point or group of points and make sure that was over the bird. The issue was when the bird started moving because this tiny dot also now had to be moved to stay on the subject. That was extremely difficult, particularly with a long and heavy lens.

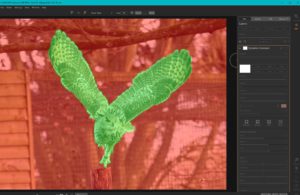

If only the camera could somehow figure out what was a bird and what was a rock or twig. Achieving this is the latest and most amazing advance in camera technology. Incredibly, many cameras now contain an AI engine that can recognise a bird in almost any position, even when it is partially concealed by foliage. Moreover, it can go beyond that and focus on the eye of the bird to make sure the key item is pin sharp. This has revolutionised bird photography, and has made razor sharp bird photographs the norm, rather than the exception. But it is still possible to ruin your nice and sharp image, particularly when it is of a sacred ibis.

The problem of exposure

Now you have a lens long enough to get the Ibis in frame, you can capture enough shots to get an interesting position, and you have the bird in focus. All done, right? Nope, there is one more factor that can kill the shots, and it is just about unique to BIF photography.

The Ibis is a bird of extreme contrasts in tone. Specifically, it has a long pointed beak which is the darkest black, and into that are set black eyes. Its wing tips are also deep black. But its wings are the purest white, and frequently catch the light to make them brilliant white. There are few other subjects in photography that have such an exposure range, and for those (such as a man in a black dinner jacket and white shirt) there is usually time to set exactly the right exposure. However, everything has to be done superfast in BIF. The light can change in an instant, and the exposure has to be changed to match.

If the white of the Ibis wing is overexposed or “blown out”, the shot is pretty much ruined. On the other hand, the physics of photographs means that you need as much light in the shot as possible, not least to show up details in the black beak. So the trick is to set the exposure so that the wing is just on the edge of being blown out, but not quite there. But how can you tell in a fraction of a second if the wing is correctly exposed? With most cameras, including pro cameras from Canon and Nikon, you can’t. What you need is an instantaneous means of seeing what the wing exposure is by a visible highlight indicator on the bird’s wing, coupled with a means of being able to instantly dial back or increase the exposure to get it just right.

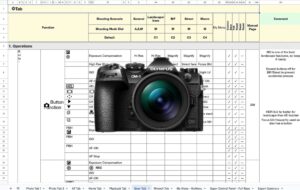

As far as I know, there is only one camera range perfectly set up to do this, and that is the Olympus OMD system. The operation and setup of fast exposure compensation for these cameras is explained in much more detail in this post. Sony cameras can do it in theory, but in my experience, it doesn’t work at all well in practice.

Bringing it all together — my perfect system for the Sacred Ibis

So to summarise, the great advances in recent years for photographing these birds have been:

There are a few other requirements for a great BIF system. These are:

Does such a perfect system exist?

No. It may never exist. High end, high-resolution professional systems like the Nikon Z8/9, the Canon R5, and the Sony A1 cannot achieve a practical burst rate of more than 20-30 frames per second, and the cameras and pro lenses are heavy, even the cheaper zoom lenses. The lower resolution Sony A9iii can get to 120 frames per second, but it is insanely expensive and requires the heavy prime lenses I mentioned above to get to 800mm.

But one system gets extremely close, with some limitations on low light photography. That is the Olympus OM1 camera, with the 300mm (or 600 FFE) F4 prime lens and 1.4 teleconverter (taking it to 840mm FFE). That gives me 9 out of the 10 items on the tick list above, and in my kind of photography, I shoot when the light is good, so I can work around the 10th. In my opinion, no system can match Olympus for the Sacred Ibis and similar birds (in good light), and certainly no other system is as versatile for other genres. Moreover, there has never been a time in photography when all this has been available at such a low price (but it’s still not cheap).

It should be noted that fabulous BIF photographs are taken every day by pros who use the giant lenses and heavy cameras from Sony, Canon, or Nikon. And even more great shots are taken with lower cost cameras from the big three, as well as from great companies like Fuji and Panasonic together with lower cost zoom lenses. And I haven’t even discussed the awesome Olympus 150-400mm f4.5 (300-800mm FFE) which ticks nearly every box except size and price (it’s £6500 and huge). However, for me, having used, owned, and in the case of Sony, exhaustively tested those systems, the pinnacle for the Sacred Ibis and many birds of its ilk is this pro Olympus system with the tiny, light and super sharp 300mm F4 prime lens.

My time in Cape Town photographing the Sacred Ibis really brought home to me the giant improvements in BIF shooting since I started shooting them 7 years ago. Some of the change has been in my technique, but the majority of the improvement has been in the incredible technology that has brought affordable systems like the OM1 to the hands and pockets of non-dentists such as myself. Long may it continue.